|

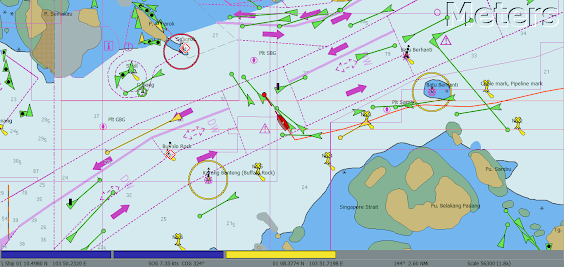

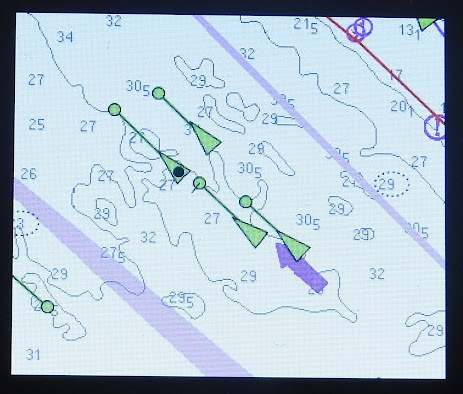

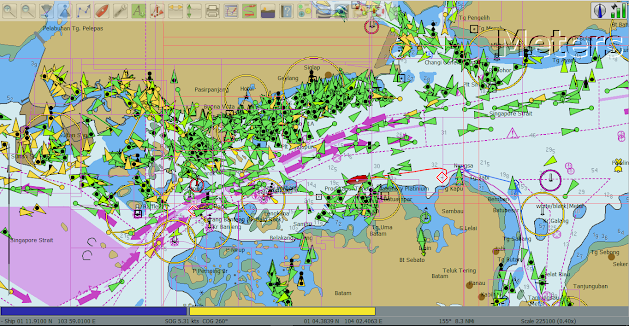

| Zoom in and get a better idea of the surrounding vessels that may pose a threat. |

What is AIS?

As the acronym suggests it’s a vessel Automatic Identification System. This system possibly one of the most substantial advances in navigation safety and an aid to sailors since the introduction of GPS (Global Positioning System) and RADAR (RAdio Detection And Ranging). Simply put, the AIS is a VHF (Very High Frequency) radio broadcasting system that transfers packets of data over a VHF Data Link (VDL). This enables AIS equipped vessels and shore-based stations to send and receive identification information that can be displayed on an integrated display, computer or chart plotter.

Getting slightly technical, AIS operates on two dedicated channels in the marine VHF frequency band. The centre of the frequency is 162.000MHz. The two dedicated VHF frequencies used for AIS are; AIS 1 161.975 MHz (channel 87B) and AIS 2 162.025 MHz (channel 88B).

When used with a graphical display, this information can help create situational awareness and provide a means to assist in collision avoidance. Additionally, AIS can be used as an aid to navigation, by providing location and additional information on buoys and lights. AIS uses a Time-Division Multiple Access (TDMA) scheme to share the VHF Data Link.

There is a multitude of automatic equipment transmitting AIS messages, to avoid conflict, the radio frequency space is organized in frames. The VDL is divided into 2250 time slots that are repeated every 60 seconds (one frame) and each AIS vessel in range sends a report to one of the time slots. At the same time, every AIS vessel in range is listening to all the timeslots and can read the reported information. As transmission can happen on two channels, there are 4500 slots per minute.

What types of AIS are there?

There is one system but as with a lot of things marine there are different classes. There are AIS mobile units and AIS stations.

AIS Base Stations: AIS used for shore stations

AIS AtoN: AIS Aids to Navigation

AIS SART: AIS Search and Rescue Transmitters

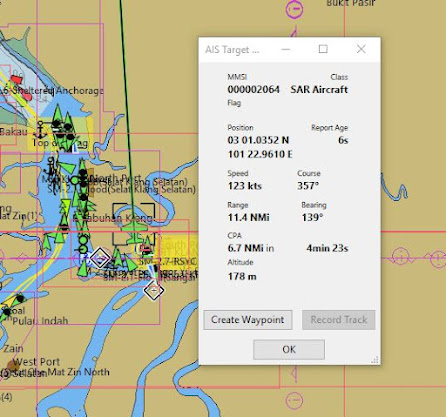

SAR aircraft: AIS fitted to Search and Rescue Aircraft

AIS MOB: AIS Man Overboard units / personal beacons /lifejacket units

Vessels of 300 gross tonnage and upwards engaged on international voyages.

Vessels of 500 gross tonnage and upwards not engaged on international voyages as well as passenger ships irrespective of size.

|

| A typical tug and tow. Tug is not big enough for mandatory fitting of an AIS for domestic use unfortunately the length of tow doesnt come into the equation |

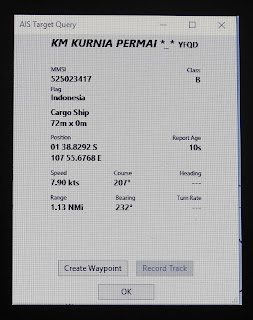

The AIS referred to in the SOLAS convention is often termed ‘AIS Class A’. AIS Class B is intended for use on non-SOLAS vessels. A non-SOLAS vessel is a vessel to which the SOLAS convention does not apply. These can include pleasure and domestic commercial vessels. AIS Class B units have less functionality than AIS Class A units but they operate and communicate with AIS Class A units and other types of AIS units. So this means you will find some smaller commercial vessels fitted with AIS Class B transponders, this is something to be aware of when you’re out there looking for a pleasure boat and it’s really an old tanker.

12.5W transmission power

Comprehensive connectivity options, for connecting to on board systems (e.g. gyro, ships primary positioning, rate of turn indicator, log, ships internal network, via satellite to ships shore office)

Large screen for viewing targets

Mini keyboard and display

Enhanced environmental protection

Pilot plug

SOTDMA (Self Organised Time Division Multiple Access) transmission type

Three receivers (2 X AIS 1 X DSC)

Enhanced transmission type ensures all AIS data should get through

Class B transceivers offer vessels most of the AIS features of Class A devices, but without some of the requirements needed for larger vessels.

Multiple connectivity option outputs to satisfy different display protocols

Same number of transmitters and receivers as Class A, but used differently

Active GPS antenna/receiver incorporated in the device

Not interfaced to a compass / gyro, (brand dependant) so heading information rarely transmitted

Not interfaced to a computer system so voyage status is cannot be input and so is not transmitted

Class B units operate using CSTDMA (Carrier Sense Time Division Multiple Access)

|

| As seen in the wild a Class B cargo ship. |

Fishing vessels may be required to carry AIS, but any vessel may switch off its AIS if the master / captain believes continual operation may compromise the safety or security of the vessel.

Base stations offer a link between vessels sailing within range and are able to relay information from AtoN’s to a monitoring or command centre that may be located inland. Shore-based AIS transceiver operates using SOTDMA. Base stations have a complex set of features and functions. Due to these features and functions base stations are able to control the AIS system and all devices operating therein. There is the ability to interrogate individual transceivers for status reports and or transmit frequency changes. FATDMA (Fixed Access Time Division Multiple Access) is also used by base stations, FATDMA allocated slots are used for repetitive messages. AIS base stations offer the chance to form an AIS network along a country's coastline that can enhance national security. Base station equipment can offer many different connections and data formats, allowing connections for many different display systems, including PCs, chart plotter displays, or wireless enabled devices.

|

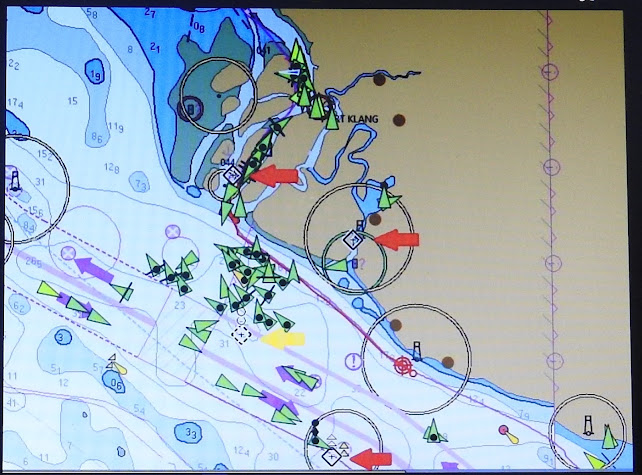

| Port Klang with AtoN's Real are high lighted by red arrows The Virtual AtoN has a yellow arrow The red and yellow arrows drawn in by author for reference |

AtoN units can be deployed on land or out at sea and have many benefits to both mariners and coastal monitoring centres. The key difference between the two types of AtoN is their power consumption. Keep in mind the AtoN stationed out at sea must rely on the power generated at the buoy, mostly done by using solar panels. An AtoN will use one of the two different types of transmission RATDMA (Random Access Time Division Multiple Access) or FATDMA (Fixed Access Time Division Multiple Access). Devices that use the FATDMA transmission type have their slots on the AIS slot map controlled by an AIS base station(s) ashore. This ensures their transmissions get through, while also keeping power consumption down. AtoN using RATDMA type transmission will use more power as they behave like a Class B device and must be powered up and running prior to sending so the unit can scan for available space on the slot map. To increase the range of an AtoN chaining can be used and this also has the added benefit of an increase in the range of base stations that monitor traffic along the coastline. These AtoN buoys / fixed beacons / light houses have the possibility of also housing sensor units that monitor metrological and hydrological data along with the AIS AtoN unit.

AIS SART: AIS Search And Rescue Transmitters

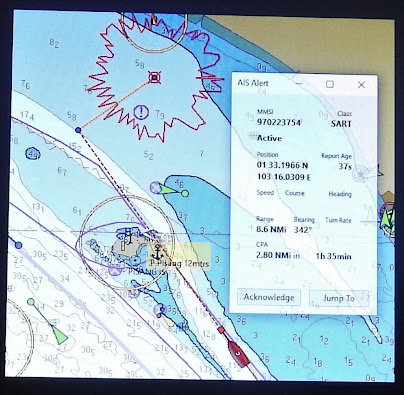

|

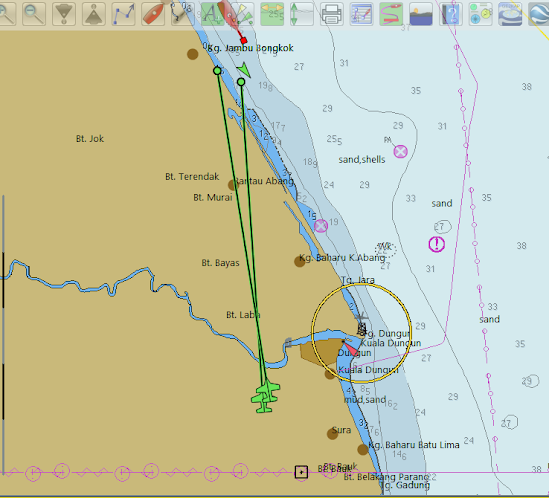

| A SAR aircraft can be seen and on the chartplotter capture. Pilot helicopters also have AIS fitted and can be seen as they are coming and going dropping off or picking up the pilot. |

In an emergency situation, mariners have predominantly used a RADAR SART as a means to alert ships of their location if they are in distress. Unfortunately the RADAR SART has to be in the beam of the SAR ships RADAR to display a position on the RADAR screen. However, an AIS SART can offer many benefits including the ability to be seen around headlands, up rivers or behind islands, it doesn’t need a RADAR beam to activate it. AIS SART offer enhanced location finding in an emergency, by transmitting the position, heading and speed of the ship in distress / life raft's with the AIS data eight times in a minute. A safety message ‘SART ACTIVE’ is sent every four minutes. This is the primary benefit over other technology as it allows SAR vessels / aircraft to track and plan a course to intersect, and rescue the vessel occupants.

|

| SART Activated Chart Plotter Drawing Passage to Distressed Vessel |

A SART will use PATDMA (Pre Announced Time Division Multiple Access) as they continuously transmit but don’t receive. A SART does not Man Overboard units / personal beacons /lifejacket units receive any data, it’s just a transmitting device. The device sends the information often to ensure that the vessel in distress is at the peak of a wave on at least one of the transmissions helping to maximise the range of the one watt transmitter.

|

| Two SAR aircraft |

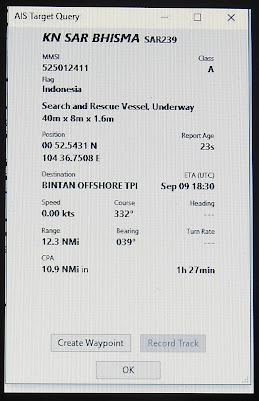

SAR aircraft: AIS fitted to Search and Rescue Aircraft to aid search and rescue tracking AIS SART’s. However most systems display a SART once activated, I know both my ship board display units come up with a warning that a SART has been activated, then the system will ask if I want to lay a course to steer to an active SART.

|

| Search and Rescue vessel |

AIS MOB:

Know the difference between an AIS PLB and a PLB

There are PLB’s (personal locating beacon) and AIS PLB’s, make sure you get to know the difference between an AIS MOB beacon, also known as an AIS PLB and a PLB so you purchase the correct one for your needs.

Step one: While these AIS units are not new on the market, before purchasing a beacon check if the one you are thinking of purchasing is authorised with AMSA and ACMA (Australian Communications and Media Authority) to be on the AIS network. (Some are not due to the transmission type)

The similarities between AIS and RADAR

The good thing is AIS has been designed and manufactured to work automatically and continuously, regardless of where a vessel is located. In the early advertisements AIS was touted as being RADAR like, however this is not the case at all. The only real similarities between AIS and RADAR is that the displays can be configured to look similar. Perhaps this is what the advertisements meant when they describe AIS RADAR. But the reality is RADAR transmits a pulse of extremely high frequency electrical energy that reflects off objects returning to the point of origin, after several pulses have been received, and after undergoing signal processing the blip or returned pulse is displayed on a RADAR screen.

|

| Vessel being shielded from RADAR by a larger vessel |

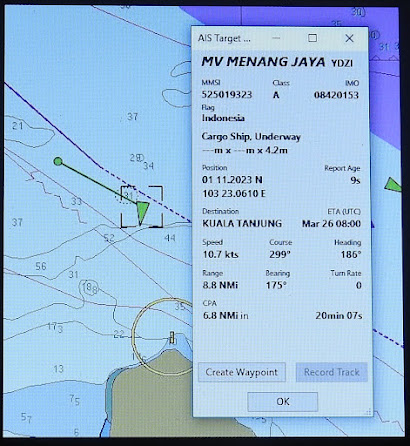

While RADAR is good the information that can be received form an AIS target can be better in some respects. In most cases we are able to, read data sent from the AIS target on the display device (chart plotter) by various means and get a host of information. The process to read the data transmitted from the target will be dependent on the chart plotter brand. On some display devices just moving the cursor over the target will display a list of data. Different brands of devices will require more or less button pressing and cursor movements but usually the important information is there at your fingertips. But don’t stop using the RADAR once you have AIS, just keep in mind it is very good at double checking the AIS target is transmitting its correct position. Or perhaps check for vessels out there that are not transmitting an AIS signal at all. For some of you headed to Asia, a word of warning; at night be on the lookout for tugs, the lights are usually correct for the type of tow, but mostly they don’t transmit AIS due to being domestic carriers. The good news is that the extremely large barges they tow can be good RADAR reflectors.

|

| A closer look and see several vessels rafted up, not easy to spot with RADAR |

With AIS information that can be called up and displayed is the target vessels, identity, position, current course, heading and speed. If your vessel is equipped with an AIS transceiver all this happens while also providing your information in real time to the other AIS system users. VHF frequencies have a longer wavelength than RADAR, AIS signals can be received from behind breakwaters, headlands, up river bends. It is also good for seeing vessels behind other ships in close quarters situations where a RADAR signal will not see or is blocked. So just this feature of the AIS signal alone can add to safer navigation by detecting the position(s) of a ship(s), even when tucked behind an island or hidden from view behind another larger ship.

If you are busy hanging on and find it’s getting difficult to check the vessels around you as the weather deteriorates. One of the features on most chart plotters or navigation software with integrated on-board AIS systems is the function to set alarms. These alarms can warn you if and when you will get too close to another vessel. These collision avoidance alarms are an advantage and can save you so a lot of time and anxiety when navigating across busy shipping lanes or in bad weather. Unfortunately this information is only as good as the data the AIS on your vessel is receiving and still requires a human for the interpretation / cross checking of the data. A vessel moving along at two knots may actually turn out to be towing another vessel on massively long cable.

The two alarms that can be set up; CPA (Closest Point of Approach) and TCPA (Time to Closest Point of Approach). It will depend on the brand and setup of the AIS system as to how these alarms are set, the best thing to do is to read the manual. Most systems will allow you to enter your own CPA and TCPA values for when the alarm will be triggered and so you need to decide how close you want to let other vessels get to you (CPA) before an alarm sounds and also how much time you need to take avoiding action (TCPA). Remember give yourself time for an out, especially when the vessels you may need to avoid are over three hundred metres long and traveling at twenty five knots.

You might decide that 1NM is plenty close enough for a large ship to pass and you want to have at least twenty minutes notice so that you have time to take avoiding action and/or call them on the radio.

Careful use of the CPA and TCPA alarm can certainly make your trips safer, however as I said before read the manual and familiarise yourself with how your particular system works. The down side to all this automated system process is that when entering a harbour or anchorage. You may want to know how to turn off the alarms temporally otherwise they are likely to drive you crazy when they keep going off reporting a moored or anchored vessel is a dangerous target.

While it’s all well and good to set CPA and TCPA alarms, in most cases you will still need to interpret the data and make the call on whether you will be crossing ahead or behind the vessel you have been tracking. It can make a big difference, crossing a quarter of a mile astern of a vessel moving at twenty five knots isn’t a problem but I wouldn’t think about trying to cross the bow at this range. One thing to keep in mind when coming up on large ships is their positioning antenna placement. You may find that a large ship has almost three hundred metres (0.16nM) of ship ahead of the position reported on the AIS.

Due to the great safety benefits offered by AIS, the network has continued to mature and expand to fulfil the design brief. Now combined with shore stations, this system offers port authorities and fully equipped maritime safety bodies the capability to manage maritime traffic and reduce the hazards of marine navigation.

A safety feature of the AIS is the AtoN (Aids to Navigation) can be transmitted over AIS. These can be physical aids like beacons, buoys, light houses fitted with an AIS transceiver or they can be computer-generated (virtual), like ones used to mark a new or temporary danger such as a shoaling bank or wreck. The computer generated AtoN can be set up and working quickly and is all done without the need for a marker/buoy to be physically placed on the dangerous point.

AIS can also be used to identify if navigational aids have moved from their charted position. As an example if a beacon or floating buoy fitted with an AIS transmitter is noticed as not being in the correct location corrective action can be put into motion quickly. Maritime safety bodies can send safety messages that might include developing storms, other weather events or search and rescue information. Additionally safety messages can be issued from either a ship or maritime safety stations. A ship that is underway but not able to manoeuvre properly due to some exceptional circumstance may issue a broadcast warning that they are now ‘not under command’.

The AIS system has many features that have the ability to bring immense benefits and collision avoidance to sailors. Important when on coastal passages and entering or traversing shipping lanes, these features are especially useful for shorthanded crews, e.g. cruising couples. AIS does not replace a proper look out, but it can add enhance situational awareness for the person on watch. Because the AIS can handle 2,250 reports per minute and may update information as often as every two seconds, real-time changes of another ship's movements can usually be immediately recognized.

The following shows what information each type of transponder will receive from the other.

Class A To Class A & B Class B To Class A & B

Position Position Position Position

Speed Speed Speed Speed

Course Course Course Course

Heading Heading Heading* Heading

MMSI MMSI MMSI MMSI

Name Name Name Name

Call Sign Call Sign Call Sign Call Sign

Vessel Type Vessel Type Vessel Type Vessel Type

IMO number IMO number

Voyage Data Voyage Data

IMO number

Name and Call Sign

Length and Beam

Type of ship

Location of position fixing antenna

MMSI number

Ship’s position, longitude, latitude, true heading with accuracy indication

Position time stamp (in UTC)

Course Over Ground (COG)

Speed Over Ground (SOG)

Rate of turn – right or left, from 0 to 720 degrees per minute

Ship’s draught

Type of cargo

Destination and ETA

Route plan (Waypoints)

Text messages free form and can be addressed to one or many destinations or to all stations in the area. This content could contain information such as a buoy missing, off station or flotsam sighted.

Here is the COL regulation rule 5: Every vessel shall at all times maintain a proper look‑out by sight and hearing as well as by all available means appropriate in the prevailing circumstances and conditions so as to make a full appraisal of the situation and of the risk of collision.

Like all things electronic there is a possibility for errors to creep into the system when things malfunction without totally failing. If you can spot the errors you may not fall into the trap like the cruiser mentioned earlier. Remember the accuracy of AIS information received is only as good as the accuracy of the AIS information transmitted in the first place. It’s not prudent for the crew on watch to assume that the positioning information received from other ships is as accurate and of the same precision as that available on their own vessel.

Operational problems seen

What type of vessel is it?

Don’t always take the ship type listed in the AIS information to be one hundred percent correct. We were heading out from Tioman Island Malaysia across the busy South China Sea shipping lane to the Anambas Island group. We had been tracking what we believed at the time a fishing vessel traveling along at two knots. Possibly trawling or so we thought at the time. They were several miles off at the time we started to pick them up on the AIS and track their course. Due to the current, weather and our sailing angle we were on a near collision course. Ok this won’t be a problem we will just point a little more on the wind and go astern. Then as time progressed we got a glimpse of a very dim light astern of the supposed fishing vessel. With the RADAR set at the highest gain range, we got a very intermittent and weak return from something tracking along at the same speed as the AIS target. This is where it got silly (very unusual), his lights were not right for a tug with tow, so we started using our spot light to try and get a glimpse of what was trailing behind our AIS target. This resulted in the tug/vessel blacking out all his lights and turning off his AIS. Well we now had a fair what we were dealing with and then it wasn’t long before the dim light on the tow also went off. So we started the motor, changed tack and was able to pass ahead of the tug. It appears that perhaps the tug/vessel skipper was paranoid about being boarded by pirates. So we think he had set the vessel type to fishing vessel, then went into hiding when a small boat (us) was trying to shine a light his way. If only he knew even with no lights on his vessel was still very visible through the binoculars.

Why don’t I always see the vessels name dimensions or other data?

This problem is due to the operation of the system, shipboard AIS units separately broadcast different AIS messages:

A 'Position Report' which includes latitude, longitude, position accuracy, time, course, speed, navigation status. Position reports are broadcasted frequently between two to ten seconds depending on the vessel’s speed or manoeuvres, or every 3 minutes if at anchor.

A 'Static and Voyage Related Report' which includes name, dimensions, type, information regarding its voyage (e.g. static draft, destination, and ETA), static and voyage related reports are sent every six minutes.

So it’s normal for an AIS to receive numerous position reports from a vessel before the vessel name, type and data associated with a static or voyage report. A fault with the AIS can also result in the missing data, one vessel we sailed with for some time had an ongoing problem and it was rare we would see any of the static vessel data blanks filled in. It turned out the wire used for the cable run from the navigation panel to the AIS was inadequate and the AIS unit would be in continuous start up loop. It would transmit a position report and when doing so the unit would shut down due to lack of voltage then restart after transmitting. So it never ran long enough to transmit the static information.

Why do we see vessels reporting they are at anchor traveling along at speed?

This would most likely be a Class A unit. Class A units allow the input of voyage related information, in this case the person in charge of inputting the information hasn’t done the job or forgot to hit the return key. The other voyage information transmitted from this vessel may or may not be correct. Usually a call to the vessel in question will result in a hasty update.

|

| Doing 13 Knots and displaying the anchor symbol. More likely it wasn't updated before setting off. |

From time to time we see the “Inland Blue Flag” set, it's a part of the European, Inland AIS standard. The “Blue Flag” signal, commonly seen on inland waters, indicates that the vessel requests a “stbd-stbd” passage or crossing. This Blue Signal is manually switched on/off, by the target. We can only assume these are not turned off when leaving Europe, or have been set on by untrained operators.

What else could cause an error? AIS position data received from another ship might not be referenced to the WGS 84 datum so if the data on your vessel is, then there will be a discrepancy in the displayed position and their real position. The discrepancy will be distance. How much distance? This will all depend on the datum they have selected their system to run on.

Why don’t the CPA and TCPA look right for a ship pointed straight at us?

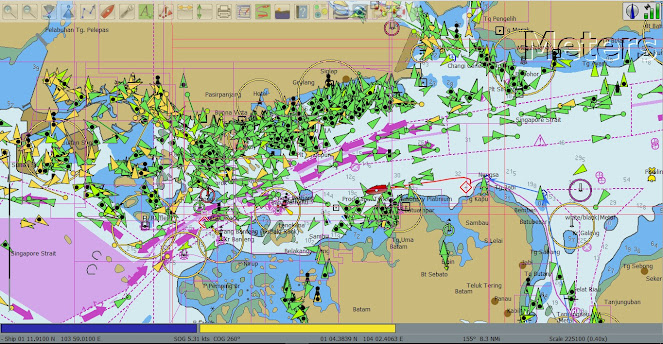

Check the vessels course and heading match up to within a couple of degrees, the closer the better. More than likely this is a set up error or the gyro connection to AIS unit wasn’t wired in correctly when the system was installed. Ships GYROs use different systems (formats) to output course data, a crossed over wire at the interface or an open circuit on one pair can cause an incorrect output without causing a total failure or error condition at the AIS unit. Be aware of this condition, a lot will depend on the brand of chart plotter or display device on your vessel. Some chart plotters don’t show targets as anything other than a triangle. If this is the case then scan your targets data when they first come into range. We have seen several ships with this error, unfortunately once we contact them and let them know of the failure they brush it aside or don’t understand. A very well spoken watch officer on a cruise ship brushed it aside treating us as if we were being a nuisance. The screen shot of the MV Menang Jaya gives a good example of this fault, the vessels COG is 299 degrees and his heading is listed as 186 degrees. His COG more than likely is being calculated by the GPS device in the AIS or the vessels navigation system, from what we saw this was correct, the heading information will most likely be coming from the on board GYRO and was wrong.

We recently sailed in Indonesia with a couple whose AIS reported the vessel was heading 000 degrees. However their COG would change to report the vessels direction of travel at the time. This turned out to be a fault with a GYRO card fitted in the all in one unit (Chartplotter, AIS, GYRO). This fault did give several ships watch keepers a fright when they thought they were going to run them down.

As I have said earlier the accuracy of AIS information received is only as good as the accuracy of the AIS information transmitted

Under SOLAS and the relevant IMO guidelines, the Master of any vessel has the discretion to turn off the AIS unit if its continual operation might compromise the vessel's safety or security.

The publicly available AIS websites (such as Marinetraffic.com) use a crowd-based approach to gather AIS information. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has condemned the display of AIS data on public websites. The AIS receivers used for this purpose are not certified AIS base stations and may not provide accurate or valid data. We have also found that the opposite can also be true when vessels are still shown as being live on the web site even when they haven’t had a received transmission for a day or more. However an even scarier feature is the ability for people to call their vessel position in on a mobile phone, without even having an AIS transceiver. Be very careful if you want to go down the AIS over the internet approach, good luck with that, it’s a recipe for disaster.

I have been told the range of my AIS is very limited

The AIS unit can have its own antenna or by using a splitter, can use the same antenna as the VHF radio. The loss in sensitivity to the VHF radio by adding a splitter is marginal and should not be a problem. However some older VHF antenna may not be suitable for AIS as the frequencies used are on the edge of the marine band and some aerials do not work well at the band edges. If you’re VHF voice transmissions are getting out and you have good range then perhaps it is time to look at the antenna you are using. Another thing to check is your cable runs. In most cases the VHF antenna is at the top of the mast, this can help with extending the range. The down side is the cable run is long and if the cable run up the mast is not low loss coax cable then this could be the source of some signal loss. All said and done a check by a radio tech / electronics tech should be able to give an answer on whether it’s the radio, splitter, cable or antenna.

If you are using a splitter check to see if it has any status lights on the front, I have seen active splitters malfunction from time to time. Splitters appear to be especially sensitive to lightning storms and the storm doesn’t need to be close. A power reset will sometimes do the trick and it will function as it should after turning it off for a little while and then powering it back on.

If you are using an AIS transceiver, the splitter must be suitable for transmit use; this is certainly worth checking if you are upgrading from a receive only unit.

Keep in mind that if the VHF radio is using the same antenna as the AIS sometimes the AIS targets will disappear from your chart plotter when using the VHF radio. This usually depends on the length of time you have been or are on the VHF. When I was using a passive antenna splitter I had problems when in a heavy shipping areas. Voice communications were interrupted by the AIS as it was still sending during a voice transmission. To get around this I installed an active splitter, this always gives priority to the VHF radio transmissions and also has a fail-safe feature where it is designed to protect/maintain the VHF connection in the event of the splitter circuit failing.

Disasters Averted

I know from experience the AIS system has aided rescue or has helped keep people out of trouble.

The first was when a catamaran was moving through the Barrier Reef area and a ship contacted them by name and let them know they must take evasive action now or they would be run down. They took evasive action and was able to power out of the ships way quickly.

Another time when moving through the Barrier Reef area up near Flinders Island, an EPIRB had been activated and through the aid of AIS the Reef VTS was able to contact the two closest boats to the activated beacon. As it turned out that was ourselves and a vessel we were traveling with at the time. The others were slightly closer and were able to find the distressed boat (broken down tinnie) and tow them to safety.

Before heading into the channel between the two main islands of the Kai group in Indonesia I was tracking the progress of a vessel already in the passage. As I was watching their progress thanks to the AIS, I noticed they were headed for a shoal area at seven knots. I called them on the VHF to let them know my charts showed they were possibly sailing into trouble. As it turned out the older chart plotter chip they were using in the cockpit did not have the shoals marked, but the newer chip used below showed the rocks and shoals clearly. If it wasn’t for the fact I was able to track their progress thanks to the AIS a disaster was averted.

|

| While not easy to see at first there are a lot of vessels rafted up together in pairs. Zoom in the chart plotter is the best way to keep on top of the problem. |

While moving through a crowded ship anchorage we were coming up to a large tanker, thanks to the AIS we were able to see a dredge was about to come out from behind the tanker at speed. Because of the proximity of the moored tanker and the lack of manoeuvrability in the anchorage the dredge was shielded from both our vision and the RADAR beam. The good thing was that we were able to take evasive action well before a close quarters situation arose.

To sum it up

The AIS only improves the safety of navigation by assisting the person on watch. As with all navigational and/or electronic equipment, the AIS has limitations. Always keep in mind that the accuracy of AIS information received is only as good as the accuracy of the AIS information transmitted in the first instance. Users must be aware that erroneous information might be transmitted by the AIS from another ship. Try not to become over dependant on the AIS as this can cause complacency on the part of the watch keeper. If the person on watch isn’t keeping a vigilant watch out on the real world, there could be developing close quarters situations when ships where the AIS, if fitted, is switched off. While there is talk of errors with the system, analyse the data available from several sources and by using the AIS as another tool (not the only tool) good decisions can be made to keep your vessel safe.

For as little as sixty australian dollars you can have a stand alone AIS receiver using a USB, RTL software defined radio and some free software loaded up on your laptop. An internal connection to OpenCPN and you have a setup that will display class A and B AIS targets on your charts in real time.

Satellite Navigation and Satellite based Augmentation

No comments:

Post a Comment